Lady Murasaki Shikibu on the Art of the Novel

Murasaki Shikibu ( 紫 式部 , English: "Lady Murasaki"; c. 973 or 978 – c. 1014 or 1031) was a Japanese novelist, poet and lady-in-waiting at the Imperial courtroom in the Heian menstruation. She is best known every bit the author of The Tale of Genji, widely considered to exist one of the world'due south first novels, written in Japanese between nigh 1000 and 1012.[ane] Murasaki Shikibu is a descriptive name; her personal name is unknown, simply she may have been Fujiwara no Kaoriko ( 藤原 香子 ), who was mentioned in a 1007 court diary as an imperial lady-in-waiting.

Heian women were traditionally excluded from learning Chinese, the written language of government, but Murasaki, raised in her erudite father'southward household, showed a precocious aptitude for the Chinese classics and managed to acquire fluency. She married in her mid-to belatedly twenties and gave birth to a girl earlier her husband died, two years subsequently they were married. Information technology is uncertain when she began to write The Tale of Genji, but it was probably while she was married or shortly after she was widowed. In most 1005, she was invited to serve every bit a lady-in-waiting to Empress Shōshi at the Royal court by Fujiwara no Michinaga, probably because of her reputation as a writer. She continued to write during her service, adding scenes from courtroom life to her work. After v or half dozen years, she left court and retired with Shōshi to the Lake Biwa region. Scholars differ on the twelvemonth of her decease; although near hold on 1014, others have suggested she was live in 1031.

Murasaki wrote The Diary of Lady Murasaki, a volume of verse, and The Tale of Genji. Within a decade of its completion, Genji was distributed throughout the provinces; within a century it was recognized as a classic of Japanese literature and had become a subject of scholarly criticism. Early in the 20th century her work was translated; a six-volume English translation was completed in 1933. Scholars go along to recognize the importance of her work, which reflects Heian court society at its peak. Since the 13th century her works have been illustrated by Japanese artists and well-known ukiyo-e woodblock masters.

Early on life [edit]

Murasaki Shikibu was born c. 973 [note 1] in Heian-kyō, Japan, into the northern Fujiwara clan descending from Fujiwara no Yoshifusa, the first 9th century Fujiwara regent.[2] The Fujiwara clan dominated court politics until the end of the 11th century through strategic marriages of their daughters into the imperial family unit and the use of regencies. In the tardily 10th century and early 11th century, Michinaga, the so-called Mido Kampaku, arranged his four daughters into marriages with emperors, giving him unprecedented power.[3] Murasaki's great-grandfather, Fujiwara no Kanesuke, had been in the top tier of the aristocracy, but her branch of the family gradually lost power and past the time of Murasaki's birth was at the middle to lower ranks of the Heian elite—the level of provincial governors.[four] The lower ranks of the nobility were typically posted away from court to undesirable positions in the provinces, exiled from the centralized power and court in Kyoto.[5]

Despite the loss of condition, the family had a reputation amid the literati through Murasaki's paternal bully-grandfather and grandfather, both of whom were well-known poets. Her great-granddad, Fujiwara no Kanesuke, had 56 poems included in 13 of the Xx-one Royal Anthologies,[6] the Collections of Xxx-half-dozen Poets and the Yamato Monogatari (Tales of Yamato).[7] Her great-grandfather and grandfather both had been friendly with Ki no Tsurayuki, who became notable for popularizing verse written in Japanese.[5] Her begetter, Fujiwara no Tametoki, attended the State Academy (Daigaku-ryō)[eight] and became a well-respected scholar of Chinese classics and verse; his own verse was anthologized.[nine] He entered public service around 968 as a minor official and was given a governorship in 996, staying in service until almost 1018.[v] [10] Murasaki'southward mother was descended from the same co-operative of northern Fujiwara as Tametoki. The couple had iii children, a son and 2 daughters.[9]

In the Heian era the utilise of names, insofar as they were recorded, did not follow a modern design. A court lady, also as beingness known by the title of her own position, if any, took a name referring to the rank or title of a male person relative. Thus "Shikibu" is non a modernistic surname, but refers to Shikibu-shō , the Ministry building of Ceremonials where Murasaki's father was a functionary. "Murasaki", an additional proper name possibly derived from the color violet associated with wisteria, the pregnant of the discussion fuji (an element of her clan proper noun), may have been bestowed on her at court in reference to the name she herself had given to the main female character in "Genji". Michinaga mentions the names of several ladies-in-waiting in a 1007 diary entry; one, Fujiwara no Takako (Kyōshi), may be Murasaki's personal name.[7] [note 2]

In Heian-era Japan, husbands and wives kept split up households; children were raised with their mothers, although the patrilineal system was still followed.[11] Murasaki was unconventional considering she lived in her male parent's household, near likely on Teramachi Street in Kyoto, with her younger brother Nobunori. Their mother died, perhaps in childbirth, when they were quite young. Murasaki had at to the lowest degree three half-siblings raised with their mothers; she was very shut to one sister who died in her twenties.[12] [13] [xiv]

Murasaki was born at a flow when Japan was becoming more than isolated, subsequently missions to Cathay had ended and a stronger national culture was emerging.[15] In the ninth and 10th centuries, Japanese gradually became a written language through the development of kana , a syllabary based on abbreviations of Chinese characters. In Murasaki's lifetime, men continued to write formally in Chinese, but kana became the written linguistic communication of intimacy and of noblewomen, setting the foundation for unique forms of Japanese literature.[16]

Chinese was taught to Murasaki'southward brother equally preparation for a career in authorities, and during her babyhood, living in her father's household, she learned and became proficient in classical Chinese.[8] In her diary she wrote, "When my brother ... was a young boy learning the Chinese classics, I was in the habit of listening to him and I became unusually proficient at understanding those passages that he plant too hard to understand and memorize. Male parent, a nigh learned man, was always regretting the fact: 'Just my luck,' he would say, 'What a pity she was not built-in a man!'"[17] With her brother she studied Chinese literature, and she probably also received pedagogy in more traditional subjects such as music, calligraphy and Japanese poetry.[12] Murasaki'south education was unorthodox. Louis Perez explains in The History of Japan that "Women ... were thought to be incapable of existent intelligence and therefore were not educated in Chinese."[18] Murasaki was aware that others saw her as "pretentious, awkward, difficult to approach, prickly, too fond of her tales, haughty, prone to versifying, disdainful, cantankerous and scornful".[xix] Asian literature scholar Thomas Inge believes she had "a forceful personality that seldom won her friends."[8]

Union [edit]

Aloof Heian women lived restricted and secluded lives, immune to speak to men simply when they were shut relatives or household members. Murasaki'south autobiographical verse shows that she socialized with women but had limited contact with men other than her father and brother; she frequently exchanged poetry with women but never with men.[12] Dissimilar most noblewomen of her status, however, she did not marry on reaching puberty; instead she stayed in her male parent'south household until her mid-twenties or maybe even to her early thirties.[12] [xx]

In 996 when her father was posted to a four-year governorship in Echizen Province, Murasaki went with him, although it was uncommon for a noblewoman of the menstruum to travel such a altitude that could accept as long as 5 days.[21] She returned to Kyoto, probably in 998, to marry her begetter'southward friend Fujiwara no Nobutaka, a much older second cousin.[five] [12] Descended from the same co-operative of the Fujiwara clan, he was a court functionary and bureaucrat at the Ministry building of Ceremonials, with a reputation for dressing extravagantly and as a talented dancer.[21] In his belatedly forties at the time of their marriage, he had multiple households with an unknown number of wives and offspring.[7] Gregarious and well-known at courtroom, he was involved in numerous romantic relationships that may have connected after his marriage to Murasaki.[12] As was customary, she would have remained in her father's household where her husband would have visited her.[7] Nobutaka had been granted more than one governorship, and past the time of his marriage to Murasaki he was probably quite wealthy. Accounts of their marriage vary: Richard Bowring writes that the marriage was happy, but Japanese literature scholar Haruo Shirane sees indications in Murasaki'due south poems that she resented her husband.[five] [12]

The couple'south daughter, Kenshi (Kataiko), was born in 999. Two years later Nobutaka died during a cholera epidemic.[12] As a married adult female Murasaki would have had servants to run the household and intendance for her daughter, giving her aplenty leisure time. She enjoyed reading and had admission to romances ( monogatari ) such as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter and The Tales of Ise. [21] Scholars believe she may take started writing The Tale of Genji before her husband'southward expiry; information technology is known she was writing after she was widowed, perhaps in a state of grief.[2] [5] In her diary she describes her feelings after her husband'south death: "I felt depressed and confused. For some years I had existed from day to 24-hour interval in listless fashion ... doing piffling more than registering the passage of fourth dimension ... The thought of my continuing loneliness was quite unbearable".[22]

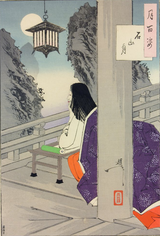

Co-ordinate to legend, Murasaki retreated to Ishiyama-dera at Lake Biwa, where she was inspired to write The Tale of Genji on an August night while looking at the moon. Although scholars dismiss the factual basis of the story of her retreat, Japanese artists often depicted her at Ishiyama Temple staring at the moon for inspiration.[13] She may have been commissioned to write the story and may have known an exiled courtier in a similar position to her hero Prince Genji.[23] Murasaki would have distributed newly written capacity of Genji to friends who in turn would have re-copied them and passed them on. By this practice the story became known and she gained a reputation as an author.[24]

In her early to mid-thirties, she became a lady-in-waiting ( nyōbō ) at court, virtually probable because of her reputation as an author.[ii] [24] Chieko Mulhern writes in Japanese Women Writers, a Biocritical Sourcebook that scholars have wondered why Murasaki made such a move at a insufficiently late menstruum in her life. Her diary evidences that she exchanged poetry with Michinaga later her hubby's expiry, leading to speculation that the two may have been lovers. Bowring sees no evidence that she was brought to courtroom as Michinaga's concubine, although he did bring her to court without following official channels. Mulhern thinks Michinaga wanted to have Murasaki at court to educate his daughter Shōshi.[25]

Court life [edit]

Heian civilisation and court life reached a peak early in the 11th century.[3] The population of Kyoto grew to around 100,000 as the nobility became increasingly isolated at the Heian Palace in government posts and courtroom service.[26] Courtiers became overly refined with picayune to do, insulated from reality, preoccupied with the minutiae of courtroom life, turning to artistic endeavors.[3] [26] Emotions were commonly expressed through the artistic use of textiles, fragrances, calligraphy, colored paper, poetry, and layering of wearable in pleasing color combinations—according to mood and season. Those who showed an inability to follow conventional aesthetics quickly lost popularity, specially at court.[18] Popular pastimes for Heian noblewomen—who adhered to rigid fashions of floor-length hair, whitened skin and blackened teeth—included having love diplomacy, writing poetry and keeping diaries. The literature that Heian courtroom women wrote is recognized every bit some of the earliest and among the best literature written in Japanese catechism.[3] [26]

Rival courts and women poets [edit]

When in 995 Michinaga's two brothers Fujiwara no Michitaka and Fujiwara no Michikane died, leaving the regency vacant, Michinaga quickly won a power struggle confronting his nephew Fujiwara no Korechika (brother to Teishi, Emperor Ichijō's wife), and, aided past his sister Senshi, he assumed power. Teishi had supported her blood brother Korechika, who was discredited and banished from courtroom in 996 following a scandal involving his shooting at the retired Emperor Kazan, causing her to lose ability.[27] Four years afterwards Michinaga sent Shōshi, his eldest daughter, to Emperor Ichijō's harem when she was about 12.[28] A twelvemonth after placing Shōshi in the purple harem, in an effort to undermine Teishi'due south influence and increment Shōshi'southward standing, Michinaga had her named Empress although Teishi already held the title. As historian Donald Shively explains, "Michinaga shocked even his admirers by arranging for the unprecedented engagement of Teishi (or Sadako) and Shōshi as concurrent empresses of the aforementioned emperor, Teishi holding the usual championship of "Lustrous Heir-bearer" kōgō and Shōshi that of "Inner Palatine" ( chūgū ), a toponymically derived equivalent coined for the occasion".[27] About v years after, Michinaga brought Murasaki to Shōshi's court, in a position that Bowring describes every bit a companion-tutor.[29]

Women of high status lived in seclusion at court and, through strategic marriages, were used to gain political power for their families. In the case of Shōshi and other such marriages to members of the imperial clan, it enabled the woman's clan to exercise influence over the emperor—this was how Michinaga, and other Fujiwara Regents, achieved their power. Despite their seclusion, some women wielded considerable influence, often accomplished through competitive salons, dependent on the quality of those attending.[30] Ichijō'south mother and Michinaga's sister, Senshi, had an influential salon, and Michinaga probably wanted Shōshi to surround herself with skilled women such as Murasaki to build a rival salon.[24]

Shōshi was sixteen to xix when Murasaki joined her courtroom.[31] Co-ordinate to Arthur Waley, Shōshi was a serious-minded young lady, whose living arrangements were divided betwixt her father'south household and her court at the Regal Palace.[32] She gathered around her talented women writers such as Izumi Shikibu and Akazome Emon—the writer of an early on colloquial history, The Tale of Flowering Fortunes.[33] The rivalry that existed among the women is evident in Murasaki's diary, where she wrote disparagingly of Izumi: "Izumi Shikibu is an agreeable alphabetic character-author; but in that location is something not very satisfactory about her. She has a gift for dashing off informal compositions in a devil-may-care running-hand; but in poesy she needs either an interesting discipline or some classic model to imitate. Indeed it does not seem to me that in herself she is really a poet at all."[34]

Sei Shōnagon, author of The Pillow Book, had been in service as lady-in-waiting to Teishi when Shōshi came to courtroom; it is possible that Murasaki was invited to Shōshi's court as a rival to Shōnagon. Teishi died in 1001, before Murasaki entered service with Shōshi, then the two writers were not there meantime, but Murasaki, who wrote nearly Shōnagon in her diary, certainly knew of her, and to an extent was influenced past her.[35] Shōnagon'due south The Pillow Book may accept been commissioned equally a type of propaganda to highlight Teishi'southward court, known for its educated ladies-in-waiting. Japanese literature scholar Joshua Mostow believes Michinaga provided Murasaki to Shōshi as an equally or better educated adult female, so equally to showcase Shōshi's court in a similar manner.[36]

The two writers had different temperaments: Shōnagon was witty, clever, and outspoken; Murasaki was withdrawn and sensitive. Entries in Murasaki'south diary evidence that the ii may not have been on expert terms. Murasaki wrote, "Sei Shōnagon ... was dreadfully complacent. She idea herself and so clever, littered her writing with Chinese characters, [which] left a neat deal to be desired."[37] Keene thinks that Murasaki's impression of Shōnagon could have been influenced by Shōshi and the women at her court, as Shōnagon served Shōshi's rival empress. Furthermore, he believes Murasaki was brought to court to write Genji in response to Shōnagon's popular Pillow Book.[35] Murasaki contrasted herself to Shōnagon in a diverseness of ways. She denigrated the pillow volume genre and, different Shōnagon, who flaunted her noesis of Chinese, Murasaki pretended to not know the linguistic communication, regarding it as pretentious and afflicted.[36]

"The Lady of the Chronicles" [edit]

Although the popularity of the Chinese language macerated in the late Heian era, Chinese ballads connected to exist pop, including those written by Bai Juyi. Murasaki taught Chinese to Shōshi who was interested in Chinese art and Juyi's ballads. Upon becoming Empress, Shōshi installed screens busy with Chinese script, causing outrage because written Chinese was considered the linguistic communication of men, far removed from the women's quarters.[38] The report of Chinese was thought to be unladylike and went against the notion that only men should have access to the literature. Women were supposed to read and write only in Japanese, which separated them through language from regime and the power structure. Murasaki, with her unconventional classical Chinese education, was 1 of the few women available to teach Shōshi classical Chinese.[39] Bowring writes it was "almost subversive" that Murasaki knew Chinese and taught the language to Shōshi.[40] Murasaki, who was reticent well-nigh her Chinese education, held the lessons between the ii women in hush-hush, writing in her diary, "Since last summer ... very secretly, in odd moments when there happened to exist no 1 about, I take been reading with Her Majesty ... There has of class been no question of formal lessons ... I accept thought it best to say nothing about the matter to everyone."[41]

A Tosa Mitsuoki illustration of Murasaki writing in solitude, late 17th century

Murasaki probably earned an cryptic nickname, "The Lady of the Chronicles" ( Nihongi no tsubone ), for pedagogy Shōshi Chinese literature.[24] A lady-in-waiting who disliked Murasaki accused her of flaunting her knowledge of Chinese and began calling her "The Lady of the Chronicles"—an innuendo to the classic Chronicles of Japan—afterwards an incident in which chapters from Genji were read aloud to the Emperor and his courtiers, i of whom remarked that the author showed a high level of education. Murasaki wrote in her diary, "How utterly ridiculous! Would I, who hesitate to reveal my learning to my women at dwelling house, ever think of doing and so at court?"[42] Although the nickname was plain meant to exist disparaging, Mulhern believes Murasaki was flattered by information technology.[24]

The attitude toward the Chinese linguistic communication was contradictory. In Teishi's court, the Chinese language had been flaunted and considered a symbol of imperial rule and superiority. Yet, in Shōshi's salon there was a great deal of hostility towards the language—perhaps owing to political expedience during a period when Chinese began to exist rejected in favor of Japanese—even though Shōshi herself was a educatee of the language. The hostility may have afflicted Murasaki and her opinion of the court, and forced her to hibernate her cognition of Chinese. Unlike Shōnagon, who was both ostentatious and flirtatious, as well as outspoken about her knowledge of Chinese, Murasaki seems to have been humble, an attitude which possibly impressed Michinaga. Although Murasaki used Chinese and incorporated information technology in her writing, she publicly rejected the linguistic communication, a commendable attitude during a period of burgeoning Japanese civilisation.[43]

Murasaki seems to have been unhappy with court life and was withdrawn and somber. No surviving records show that she entered poetry competitions; she appears to have exchanged few poems or letters with other women during her service.[five] In general, unlike Shōnagon, Murasaki gives the impression in her diary that she disliked courtroom life, the other ladies-in-waiting, and the drunken carousal. She did, however, go close friends with a lady-in-waiting named Lady Saishō, and she wrote of the winters that she enjoyed, "I dear to see the snowfall hither".[44] [45]

According to Waley, Murasaki may not take been unhappy with courtroom life in general only bored in Shōshi'south court. He speculates she would have preferred to serve with the Lady Senshi, whose household seems to accept been less strict and more light-hearted. In her diary, Murasaki wrote about Shōshi'southward courtroom, "[she] has gathered round her a number of very worthy young ladies ... Her Majesty is starting time to acquire more than experience of life, and no longer judges others by the same rigid standards as before; merely meanwhile her Courtroom has gained a reputation for farthermost dullness".[46]

Murasaki disliked the men at court, whom she thought were drunken and stupid. However, some scholars, such as Waley, are certain she was involved romantically with Michinaga. At the least, Michinaga pursued her and pressured her strongly, and her flirtation with him is recorded in her diary as late equally 1010. Nevertheless, she wrote to him in a poem, "Yous have neither read my book, nor won my love."[47] In her diary she records having to avoid advances from Michinaga—one night he sneaked into her room, stealing a newly written chapter of Genji. [48] However, Michinaga's patronage was essential if she was to proceed writing.[49] Murasaki described her daughter'due south court activities: the lavish ceremonies, the complicated courtships, the "complexities of the matrimony system",[twenty] and in elaborate item, the nascency of Shōshi'southward 2 sons.[48]

It is probable that Murasaki enjoyed writing in confinement.[48] She believed she did not fit well with the general temper of the court, writing of herself: "I am wrapped up in the study of ancient stories ... living all the fourth dimension in a poetical world of my ain scarcely realizing the existence of other people .... But when they get to know me, they detect to their extreme surprise that I am kind and gentle".[l] Inge says that she was besides outspoken to make friends at court, and Mulhern thinks Murasaki's court life was insufficiently quiet compared to other court poets.[8] [24] Mulhern speculates that her remarks about Izumi were not so much directed at Izumi'south verse merely at her behavior, lack of morality and her court liaisons, of which Murasaki disapproved.[33]

Rank was important in Heian courtroom society and Murasaki would not accept felt herself to have much, if anything, in mutual with the higher ranked and more powerful Fujiwaras.[51] In her diary, she wrote of her life at court: "I realized that my co-operative of the family was a very apprehensive ane; but the thought seldom troubled me, and I was in those days far indeed from the painful consciousness of inferiority which makes life at Court a continual torment to me."[52] A court position would take increased her social standing, but more importantly she gained a greater feel to write about.[24] Court life, every bit she experienced it, is well reflected in the chapters of Genji written subsequently she joined Shōshi. The proper name Murasaki was almost probably given to her at a court dinner in an incident she recorded in her diary: in 1008 the well-known court poet Fujiwara no Kintō inquired after the "Immature Murasaki"—an allusion to the graphic symbol named Murasaki in Genji—which would have been considered a compliment from a male person court poet to a female author.[24]

Later life and death [edit]

Genji-Garden at Rozan-ji, a temple in Kyoto associated with her erstwhile mansion

When Emperor Ichijō died in 1011, Shōshi retired from the Royal Palace to live in a Fujiwara mansion in Biwa, most likely accompanied by Murasaki, who is recorded as being there with Shōshi in 1013.[49] George Aston explains that when Murasaki retired from court she was once again associated with Ishiyama-dera: "To this beautiful spot, it is said, Murasaki no Shikibu [sic] retired from courtroom life to devote the remainder of her days to literature and faith. There are sceptics, nonetheless, Motoori being i, who decline to believe this story, pointing out ... that it is irreconcilable with known facts. On the other hand, the very sleeping room in the temple where the Genji was written is shown—with the ink-slab which the author used, and a Buddhist Sutra in her handwriting, which, if they do non satisfy the critic, even so are sufficient to carry confidence to the minds of ordinary visitors to the temple."[53]

Murasaki may have died in 1014. Her father made a hasty return to Kyoto from his postal service at Echigo Province that twelvemonth, possibly considering of her death. Writing in A Bridge of Dreams: A Poetics of "The Tale of Genji", Shirane mentions that 1014 is generally accepted as the date of Murasaki Shikibu's decease and 973 equally the date of her nascence, making her 41 when she died.[49] Bowring considers 1014 to be speculative, and believes she may have lived with Shōshi until as tardily as 1025.[54] Waley agrees given that Murasaki may accept attended ceremonies with Shōshi held for Shōshi's son, Emperor Go-Ichijō around 1025.[50]

Murasaki'southward brother Nobunori died in around 1011, which, combined with the decease of his daughter, may take prompted her father to resign his postal service and take vows at Miidera temple where he died in 1029.[2] [49] Murasaki'south daughter entered courtroom service in 1025 as a moisture nurse to the future Emperor Go-Reizei (1025–1068). She went on to go a well-known poet as Daini no Sanmi.[55]

Works [edit]

3 works are attributed to Murasaki: The Tale of Genji, The Diary of Lady Murasaki and Poetic Memoirs, a drove of 128 poems.[48] Her piece of work is considered important for its reflection of the creation and development of Japanese writing, during a menstruum when Japanese shifted from an unwritten colloquial to a written language.[30] Until the 9th century, Japanese language texts were written in Chinese characters using the human being'yōgana writing system.[56] A revolutionary achievement was the development of kana , a true Japanese script, in the mid-to late 9th century. Japanese authors began to write prose in their own language, which led to genres such as tales ( monogatari ) and poetic journals ( Nikki Bungaku ).[57] [58] [59] Historian Edwin Reischauer writes that genres such every bit the monogatari were distinctly Japanese and that Genji, written in kana , "was the outstanding piece of work of the period".[xvi]

Diary and poetry [edit]

13th century illustration ( emakimono ) of The Diary of Lady Murasaki showing Empress Shōshi with the infant Emperor Go-Ichijō and ladies-in-waiting secluded behind a kichō .

Murasaki began her diary after she entered service at Shōshi'south court.[48] Much of what is known about her and her experiences at court comes from the diary, which covers the menses from nigh 1008 to 1010. The long descriptive passages, some of which may have originated every bit letters, cover her relationships with the other ladies-in-waiting, Michinaga's temperament, the birth of Shōshi's sons—at Michinaga'south mansion rather than at the Purple Palace—and the process of writing Genji, including descriptions of passing newly written capacity to calligraphers for transcriptions.[48] [60] Typical of contemporary courtroom diaries written to honour patrons, Murasaki devotes one-half to the nascence of Shōshi's son Emperor Go-Ichijō, an upshot of enormous importance to Michinaga: he had planned for information technology with his daughter's marriage which fabricated him grandfather and de facto regent to an emperor.[61]

Poetic Memoirs is a collection of 128 poems Mulhern describes as "bundled in a biographical sequence".[48] The original set has been lost. According to custom, the verses would have been passed from person to person and oft copied. Some announced written for a lover—possibly her hubby before he died—but she may accept merely followed tradition and written uncomplicated dear poems. They incorporate biographical details: she mentions a sis who died, the visit to Echizen province with her male parent and that she wrote poesy for Shōshi. Murasaki's poems were published in 1206 by Fujiwara no Teika, in what Mulhern believes to be the collection that is closest to the original class; at around the same time Teika included a selection of Murasaki's works in an imperial anthology, New Collections of Aboriginal and Modern Times.[48]

The Tale of Genji [edit]

Murasaki is best known for her The Tale of Genji, a three-part novel spanning 1100 pages and 54 chapters,[62] [63] which is thought to take taken a decade to complete. The primeval chapters were possibly written for a private patron either during her marriage or soon after her husband's decease. She continued writing while at courtroom and probably finished while notwithstanding in service to Shōshi.[64] She would have needed patronage to produce a work of such length. Michinaga provided her with costly paper and ink, and with calligraphers. The first handwritten volumes were probably assembled and leap by ladies-in-waiting.[49]

Late 17th century or early 18th century silk gyre painting of a scene from chapter 34 of The Tale of Genji showing men playing in the garden watched by a adult female sitting backside a screen.

In his The Pleasures of Japanese Literature, Keene claims Murasaki wrote the "supreme piece of work of Japanese fiction" by drawing on traditions of waka court diaries, and earlier monogatari —written in a mixture of Chinese script and Japanese script—such every bit The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter or The Tales of Ise.[65] She drew on and blended styles from Chinese histories, narrative poetry and gimmicky Japanese prose.[62] Adolphson writes that the juxtaposition of formal Chinese manner with mundane subjects resulted in a sense of parody or satire, giving her a distinctive voice.[66] Genji follows the traditional format of monogatari —telling a tale—particularly axiomatic in its utilize of a narrator, but Keene claims Murasaki adult the genre far across its bounds, and by doing so created a grade that is utterly modern. The story of the "shining prince" Genji is set in the late 9th to early 10th centuries, and Murasaki eliminated from it the elements of fairy tales and fantasy frequently found in earlier monogatari .[67]

The themes in Genji are common to the menstruation, and are defined past Shively as encapsulating "the tyranny of time and the inescapable sorrow of romantic love".[68] The main theme is that of the fragility of life, "the sorrow of human existence" ( mono no aware ), a term used over a thousand times in Genji.[69] Keene speculates that in her tale of the "shining prince", Murasaki may have created for herself an idealistic escape from court life, which she institute less than savory. In Prince Genji she formed a gifted, comely, refined, notwithstanding human and sympathetic protagonist. Keene writes that Genji gives a view into the Heian period; for example dear affairs flourished, although women typically remained unseen backside screens, curtains or fusuma .[67]

Helen McCullough describes Murasaki'due south writing as of universal appeal and believes The Tale of Genji "transcends both its genre and historic period. Its basic subject thing and setting—love at the Heian court—are those of the romance, and its cultural assumptions are those of the mid-Heian period, simply Murasaki Shikibu's unique genius has made the work for many a powerful statement of human relationships, the impossibility of permanent happiness in love ... and the vital importance, in a world of sorrows, of sensitivity to the feelings of others."[70] Prince Genji recognizes in each of his lovers the inner beauty of the woman and the fragility of life, which according to Keene, makes him heroic. The story was popular: Emperor Ichijō had it read to him, even though information technology was written in Japanese. By 1021 all the capacity were known to be complete and the work was sought afterward in the provinces where information technology was deficient.[67] [71]

Legacy [edit]

Murasaki'south reputation and influence accept non diminished since her lifetime when she, with other Heian women writers, was instrumental in developing Japanese into a written linguistic communication.[72] Her writing was required reading for court poets as early on equally the twelfth century every bit her work began to exist studied past scholars who generated authoritative versions and criticism. Inside a century of her death she was highly regarded every bit a classical writer.[71] In the 17th century, Murasaki's piece of work became allegorical of Confucian philosophy and women were encouraged to read her books. In 1673, Kumazawa Banzan argued that her writing was valuable for its sensitivity and delineation of emotions. He wrote in his Discursive Commentary on Genji that when "human feelings are not understood the harmony of the 5 Human being Relationships is lost."[73]

Early 12th century handscroll scene from Genji, showing lovers separated from ladies-in-waiting past 2 screens, a kichō and a byōbu .

The Tale of Genji was copied and illustrated in diverse forms as early on as a century later Murasaki's death. The Genji Monogatari Emaki, is a late Heian era 12th century handscroll, consisting of four scrolls, 19 paintings, and 20 sheets of calligraphy. The illustrations, definitively dated to between 1110 and 1120, take been tentatively attributed to Fujiwara no Takachika and the calligraphy to various well-known contemporary calligraphers. The whorl is housed at the Gotoh Museum and the Tokugawa Art Museum.[74]

Female virtue was tied to literary cognition in the 17th century, leading to a need for Murasaki or Genji inspired artifacts, known every bit genji-e .Dowry sets decorated with scenes from Genji or illustrations of Murasaki became particularly popular for noblewomen: in the 17th century genji-e symbolically imbued a bride with an increased level of cultural status; past the 18th century they had come to symbolize marital success. In 1628, Tokugawa Iemitsu'southward daughter had a set of lacquer boxes made for her wedding ceremony; Prince Toshitada received a pair of silk genji-due east screens, painted past Kanō Tan'yū as a wedding gift in 1649.[75]

Murasaki became a popular subject of paintings and illustrations highlighting her equally a virtuous woman and poet. She is often shown at her desk-bound in Ishimyama Temple, staring at the moon for inspiration. Tosa Mitsuoki made her the subject of hanging scrolls in the 17th century.[76] The Tale of Genji became a favorite subject of Japanese ukiyo-due east artists for centuries with artists such every bit Hiroshige, Kiyonaga, and Utamaro illustrating various editions of the novel.[77] While early Genji art was considered symbolic of courtroom civilization, by the middle of the Edo period the mass-produced ukiyo-e prints made the illustrations accessible for the samurai classes and commoners.[78]

In Envisioning the "Tale of Genji" Shirane observes that "The Tale of Genji has become many things to many different audiences through many different media over a thousand years ... unmatched by whatever other Japanese text or antiquity."[78] The piece of work and its author were popularized through its illustrations in various media: emaki (illustrated handscrolls); byōbu-eastward (screen paintings), ukiyo-e (woodblock prints); films, comics, and in the modernistic period, manga.[78] In her fictionalized account of Murasaki's life, The Tale of Murasaki: A Novel, Liza Dalby has Murasaki involved in a romance during her travels with her father to Echizen Province.[23]

17th century ink and gold newspaper fan showing Murasaki's writing

The Tale of the Genji is recognized equally an enduring classic. McCullough writes that Murasaki "is both the quintessential representative of a unique order and a writer who speaks to universal human concerns with a timeless voice. Japan has not seen another such genius."[64] Keene writes that The Tale of Genji continues to captivate, considering, in the story, her characters and their concerns are universal. In the 1920s, when Waley's translation was published, reviewers compared Genji to Austen, Proust, and Shakespeare.[79] Mulhern says of Murasaki that she is like to Shakespeare, who represented his Elizabethan England, in that she captured the essence of the Heian court and as a novelist "succeeded perhaps fifty-fifty beyond her own expectations."[80] Like Shakespeare, her piece of work has been the subject area of reams of criticism and many books.[80]

The pattern of the 2000-yen note was created in Murasaki's honour.

Kyoto held a year-long celebration commemorating the 1000th anniversary of Genji in 2008, with poetry competitions, visits to the Tale of Genji Museum in Uji and Ishiyama-dera (where a life size rendition of Murasaki at her desk was displayed), and women dressing in traditional 12-layer Heian court jūnihitoe and talocrural joint-length wigs. The author and her piece of work inspired museum exhibits and Genji manga spin-offs.[14] The design on the contrary of the first 2000 yen note commemorated her and The Tale of Genji.[81] A establish bearing purple berries has been named after her.[82]

A Genji Album, only in the 1970s dated to 1510, is housed at Harvard Academy. The album is considered the earliest of its kind and consists of 54 paintings by Tosa Mitsunobu and 54 sheets of calligraphy on shikishi newspaper in v colors, written by master calligraphers. The leaves are housed in a case dated to the Edo flow, with a silk frontispiece painted by Tosa Mitsuoki, dated to effectually 1690. The album contains Mitsuoki's authentication slips for his ancestor'southward 16th century paintings.[83]

Gallery [edit]

-

Hiroshige ukiyo-e print (1852) shows an interior courtroom scene from The Tale of Genji.

-

In this 1795 woodcut, Murasaki is shown in word with five male court poets.

-

Murasaki Shikibu composing The Tale of Genji, by Yashima Gakutei (1786–1868).

Notes [edit]

- ^ Bowring believes her date of birth about probable to have been 973; Mulhern places it somewhere between 970 and 978, and Waley claims it was 978. See Bowring (2004), 4; Mulhern (1994), 257; Waley (1960), vii.

- ^ Seven women were named in the entry, with the bodily names of iv women known. Of the remaining three women, i was not a Fujiwara, one held a loftier rank and therefore had to be older, leaving the possibility that the third, Fujiwara no Takako, was Murasaki. See Tsunoda (1963), 1–27

References [edit]

- ^ "In Celebration of The Tale of Genji, the World's First Novel". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2019-10-12 .

- ^ a b c d Shirane (2008b), 293

- ^ a b c d Henshall (1999), 24–25

- ^ Shirane (1987), 215

- ^ a b c d e f k Bowring (2004), 4

- ^ Chokusen Sakusha Burui 勅撰作者部類

- ^ a b c d Mulhern (1994), 257–258

- ^ a b c d Inge (1990), 9

- ^ a b Mulhern (1991), 79

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 111

- ^ Ueno (2009), 254

- ^ a b c d eastward f one thousand h Shirane (1987), 218

- ^ a b Puette (1983), 50–51

- ^ a b Dark-green, Michelle. "Kyoto Celebrates a 1000-Year Love Affair". (December 31, 2008). The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2011

- ^ Bowring (1996), xii

- ^ a b Reischauer (1999), 29–29

- ^ qtd in Bowring (2004), 11–12

- ^ a b Perez (1998), 21

- ^ qtd in Inge (1990), ix

- ^ a b Knapp, Bettina. "Lady Murasaki's The Tale of the Genji". Symposium. (1992). (46).

- ^ a b c Mulhern (1991), 83–85

- ^ qtd in Mulhern (1991), 84

- ^ a b Tyler, Royall. "Murasaki Shikibu: Brief Life of a Legendary Novelist: c. 973 – c. 1014". (May 2002) Harvard Magazine. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mulhern (1994), 258–259

- ^ Bowring (2004), 4; Mulhern (1994), 259

- ^ a b c Lockard (2008), 292

- ^ a b Shively and McCullough (1999), 67–69

- ^ McCullough (1990), 201

- ^ Bowring (1996), xiv

- ^ a b Bowring (1996), xv–xvii

- ^ According to Mulhern Shōshi was nineteen when Murasaki arrived; Waley states she was 16. See Mulhern (1994), 259 and Waley (1960), vii

- ^ Waley (1960), vii

- ^ a b Mulhern (1994), 156

- ^ Waley (1960), xii

- ^ a b Keene (1999), 414–415

- ^ a b Mostow (2001), 130

- ^ qtd in Keene (1999), 414

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 110, 119

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 110

- ^ Bowring (2004), 11

- ^ qtd in Waley (1960), nine–ten

- ^ qtd in Mostow (2001), 133

- ^ Mostow (2001), 131, 137

- ^ Waley (1960), thirteen

- ^ Waley (1960), xi

- ^ Waley (1960), 8

- ^ Waley (1960), x

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mulhern (1994), 260–261

- ^ a b c d e Shirane (1987), 221–222

- ^ a b Waley (1960), xv

- ^ Bowring (2004), 3

- ^ Waley (1960), xiv

- ^ Aston (1899), 93

- ^ Bowring (2004), five

- ^ Mulhern (1996), 259

- ^ Mason (1997), 81

- ^ Kodansha International (2004), 475, 120

- ^ Shirane (2008b), ii, 113–114

- ^ Frédéric (2005), 594

- ^ McCullough (1990), 16

- ^ Shirane (2008b), 448

- ^ a b Mulhern (1994), 262

- ^ McCullough (1990), nine

- ^ a b Shively (1999), 445

- ^ Keene (1988), 75–79, 81–84

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 121–122

- ^ a b c Keene (1988), 81–84

- ^ Shively (1990), 444

- ^ Henshall (1999), 27

- ^ McCullough (1999), nine

- ^ a b Bowring (2004), 79

- ^ Bowring (2004), 12

- ^ qtd in Lillehoj (2007), 110

- ^ Frédéric (2005), 238

- ^ Lillehoj (2007), 110–113

- ^ Lillehoj, 108–109

- ^ Geczy (2008), 13

- ^ a b c Shirane (2008a), ane–ii

- ^ Keene (1988), 84

- ^ a b Mulhern (1994), 264

- ^ "Japanese Feminist to Beautify Yen". (Feb 11, 2009). CBSNews.com. Retrieved August xi, 2011.

- ^ Kondansha (1983), 269

- ^ McCormick (2003), 54–56

Sources [edit]

- Adolphson, Mikhael; Kamens, Edward and Matsumoto, Stacie. Heian Nippon: Centers and Peripheries. (2007). Honolulu: Hawaii UP. ISBN 978-0-8248-3013-7

- Aston, William. A History of Japanese Literature. (1899). London: Heinemann.

- Bowring, Richard John (ed). "Introduction". in The Diary of Lady Murasaki. (1996). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-fourteen-043576-4

- Bowring, Richard John (ed). "Introduction". in The Diary of Lady Murasaki. (2005). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-043576-4

- Bowring, Richard John (ed). "The Cultural Groundwork". in The Tale of Genji. (2004). Cambridge: Cambridge Up. ISBN 978-0-521-83208-3

- Frédéric, Louis. Nihon Encyclopedia. (2005). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Upward. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-five

- Geczy, Adam. Art: Histories, Theories and Exceptions. (2008). London: Oxford International Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84520-700-vii

- Inge, Thomas. "Lady Murasaki and the Arts and crafts of Fiction". (May 1990) Atlantic Review. (55). 7–fourteen.

- Henshall, Kenneth G. A History of Japan. (1999). New York: St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-21986-iv

- Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan. (1983) New York: Kōdansha. ISBN 978-0-87011-620-9

- Keene, Donald. Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest times to the Late Sixteenth Century. (1999). New York: Columbia Upward. ISBN 978-0-231-11441-seven

- Keene, Donald. The Pleasures of Japanese Literature. (1988). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 978-0-231-06736-ii

- The Nihon Volume: A Comprehensive Pocket Guide. (2004). New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2847-1

- Lillehoj, Elizabeth. Critical Perspectives on Classicism in Japanese Painting, 1600–17. (2004). Honolulu: Hawaii Upwardly. ISBN 978-0-8248-2699-iv

- Lockard, Craig. Societies, Networks, and Transitions, Volume I: To 1500: A Global History. (2008). Boston: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-1-4390-8535-six

- Mason, R.H.P. and Caiger, John Godwin. A History of Japan. (1997). North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-2097-4

- McCormick, Melissa. "Genji Goes W: The 1510 Genji Album and the Visualization of Court and Uppercase". (March 2003). Art Bulletin. (85). 54–85

- McCullough, Helen. Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology. (1990). Stanford CA: Stanford Upwards. ISBN 978-0-8047-1960-5

- Mostow, Joshua. "Mother Tongue and Father Script: The relationship of Sei Shonagon and Murasaki Shikibu". in Copeland, Rebecca L. and Ramirez-Christensen Esperanza (eds). The Father-Daughter Plot: Japanese Literary Women and the Law of the Male parent. (2001). Honolulu: Hawaii Upwards. ISBN 978-0-8248-2438-9

- Mulhern, Chieko Irie. Heroic with Grace: Legendary Women of Nippon. (1991). Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-87332-527-ane

- Mulhern, Chieko Irie. Japanese Women Writers: a Bio-disquisitional Sourcebook. (1994). Westport CT: Greenwood Printing. ISBN 978-0-313-25486-4

- Perez, Louis G. The History of Nihon. (1990). Westport CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30296-i

- Puette, William J. The Tale of Genji: A Reader'due south Guide. (1983). North Clarendon VT: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3331-8

- Reschauer, Edwin. Japan: The Story of a Nation. (1999). New York: McGraw-Loma. ISBN 978-0-07-557074-5

- Shirane, Haruo. The Bridge of Dreams: A Poetics of "The Tale of Genji". (1987). Stanford CA: Stanford UP. ISBN 978-0-8047-1719-9

- Shirane, Haruo. Envisioning the Tale of Genji: Media, Gender, and Cultural Product. (2008a). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 978-0-231-14237-iii

- Shirane, Haruo. Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600. (2008b). New York: Columbia Upwards. ISBN 978-0-231-13697-six

- Shively, Donald and McCullough, William H. The Cambridge History of Nihon: Heian Japan. (1999). Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-22353-nine

- Tsunoda, Bunei. "Real name of Murasahiki Shikibu". Kodai Bunka (Cultura antiqua). (1963) (55). i–27.

- Ueno, Chizuko. The Mod Family unit in Japan: Its Rising and Autumn. (2009). Melbourne: Transpacific Press. ISBN 978-one-876843-56-4

- Waley, Arthur. "Introduction". in Shikibu, Murasaki, The Tale of Genji: A Novel in Half dozen Parts. translated by Arthur Waley. (1960). New York: Modern Library.

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murasaki_Shikibu

0 Response to "Lady Murasaki Shikibu on the Art of the Novel"

Post a Comment